Melba was nine when she met the future Queen Elizabeth II.

(Guest article by Henry Irving, Leeds Beckett University)

It was 1943 and she had travelled to a special event in Cardiff to be given a prize by the princess. Melba, who loved to read, was given the complete works of William Shakespeare and a framed certificate for her school. She also had a gift for the princess: a unique book about recycling written by Welsh schoolchildren.

Melba had won a competition designed to show why recycling was important in wartime. She had written an essay calling on children ‘to help and not look on’. She explained that recycling saved materials and allowed ships to carry more useful items. What could children do? Well, Melba asked them to make sure their recycling was properly separated. She was clear: ‘We must not waste the tiniest bit of rubber, the smallest piece of material, or the most insignificant bone’.

Recycling was an important part of life in the Second World War. As Melba explained, Britain faced shortages of many raw materials because of enemy attacks on supply ships. The government responded by asking people to separate wastepaper, rags, tins, bones, rubber and food waste from their dustbins. Very few people had done this before the war. But, by the time Melba wrote her essay, around 80 per cent of households were recycling at least something.

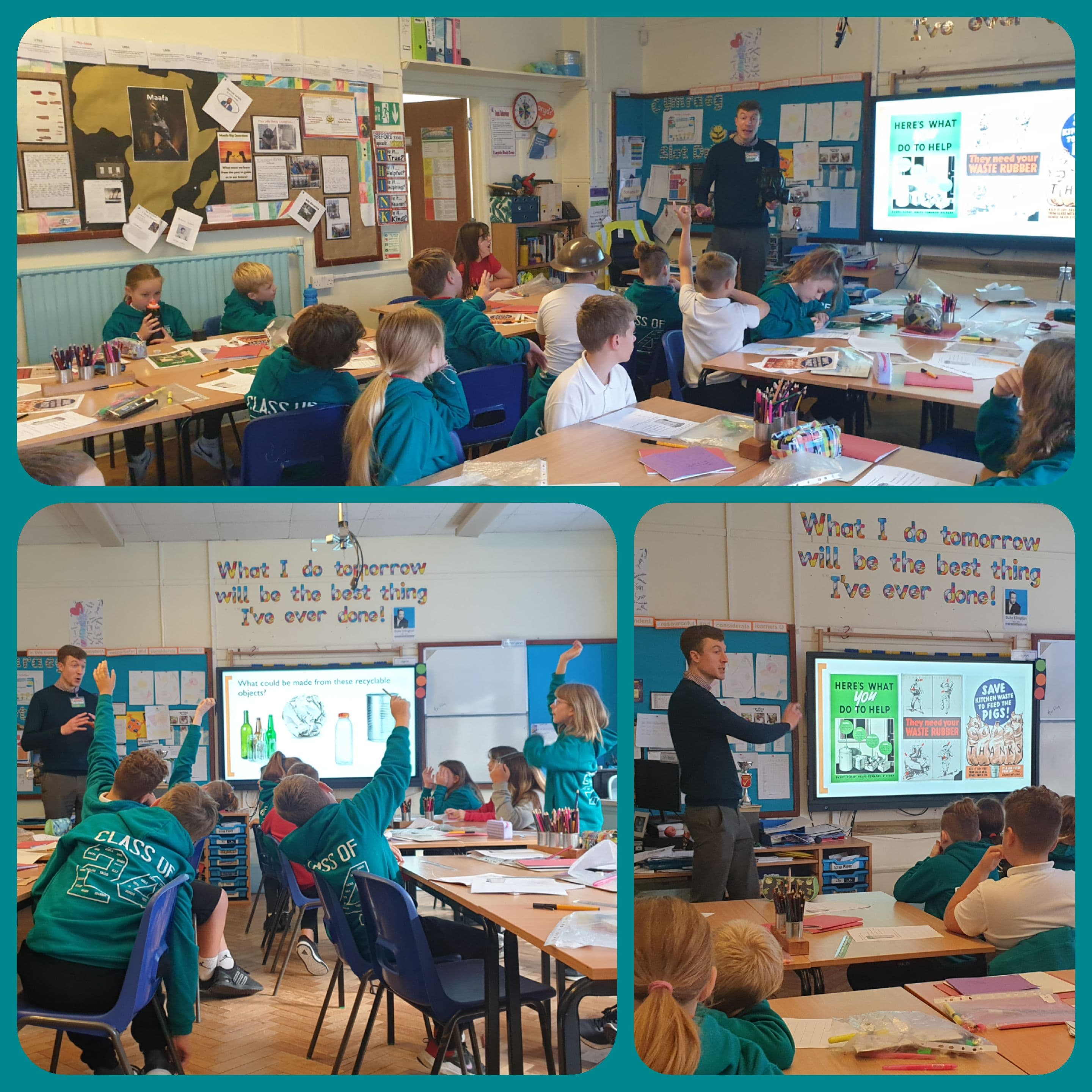

I am working with WRAP to see what lessons this history has for today. I have also been lucky enough to visit Melba’s old school to talk to its current pupils. I shared Melba’s story with a group of ten- and eleven-year-olds as part of a day of activities about recycling. They read her essay and learnt more about the different reasons for recycling in the 1940s. They also designed a series of posters inspired by the wartime messages Melba grew up with.

This was much more than a history lesson. The children linked what was happening 80 years ago with what is happening today. Recycling still saves materials. But we are now more interested in saving energy than protecting ships. We also learnt how Welsh food waste is recycled to create electricity, which is a far cry from its use as pig food in the Second World War!

As the day went on, we realised something very important. The fact a banana peel has the power to charge two phones if recycled properly is not that different from the way bones were recycled to make explosives in the 1940s. The point is that we cannot always imagine how useful our rubbish can be. Melba understood this during the war and the children I spoke to realise it today. The school no longer has her certificate, but Melba’s legacy clearly lives on.

Over the coming weeks children will be invited to join the Mighty Food Waste Mission.

About the author

Henry Irving is a historian based at Leeds Beckett University. He is an expert in the history of waste and recycling. He is working with WRAP on a project called ‘From Salvage to a Circular Economy’ which is funded by the British Academy. The aim of the project is to use his knowledge of history to enhance recycling today.